Yuyang Zhang “umm no”

By LINDSAY COSTELLO

Installation view of umm no, photo by Mario Gallucci courtesy of the gallery.

Yuyang Zhang, a Portland-based artist from Wuhan, China, recently explained that taking oneself seriously is a central tenet of Chinese culture and politics. He opted to challenge this stereotype through a solo exhibition, umm no, on view at Fuller Rosen Gallery. Zhang draws on Chinese Communist Party propaganda, emojis, and American political memes to create tongue-in-cheek paintings and digital collages; the results, Zhang hopes, demonstrate that Chinese people can be witty, casual, and poke fun at themselves. While umm no sources imagery from Chinese and American culture, the exhibition holds a universal appeal. It manages to inspire laughter in a historically painful time, but doesn’t deny the ongoing gravity of cultural conflict, authoritarianism, and xenophobia.

Zhang senses what he calls a “double positioning”—as a Wuhan native living in the United States, he observes two perspectives, rife with ideological differences and parallels. The tone of our last year has been particularly xenophobic toward Chinese people. Trump has used and encouraged explicitly anti-Chinese language, and we’ve seen an uptick in violent crimes against Asian Americans. Authoritarianism denies our objectivity, our humanity, our laughter; Zhang knew that he wanted to make work about this time, and wondered how he could form a social critique without losing his artistic vision. He noticed the ways in which pandemic uncertainty encourages nostalgia—we scroll through old images, thinking about the “before times.” At the same time, we “doomscroll” to remain aware of the current state of the world.

Zhang is foremost a photographer, a difficult medium to practice during quarantine. He decided to look closely at CCP propaganda posters, which are an inescapable part of Chinese history—despite being a millennial, Zhang says, the shadow of this time in Chinese history persists. Who creates these narratives, he wondered? Can an artist claim ownership of propaganda and change its meanings?

From these thoughts, Zhang developed a three-action collage process: destruction, reassemble, layer. His collages contain “actors,” bright-smiled and commercial, sourced from propaganda imagery, combined with screenshots of phone notifications and “stages,” sourced from Zhang’s own photography. He views these “stages” (a parking garage, a ballot drop-off, a dumpster) as places where his “actors” live. Zhang’s collages allow dissimilar elements to converge, elevating or changing meanings to create a holistic disruption.

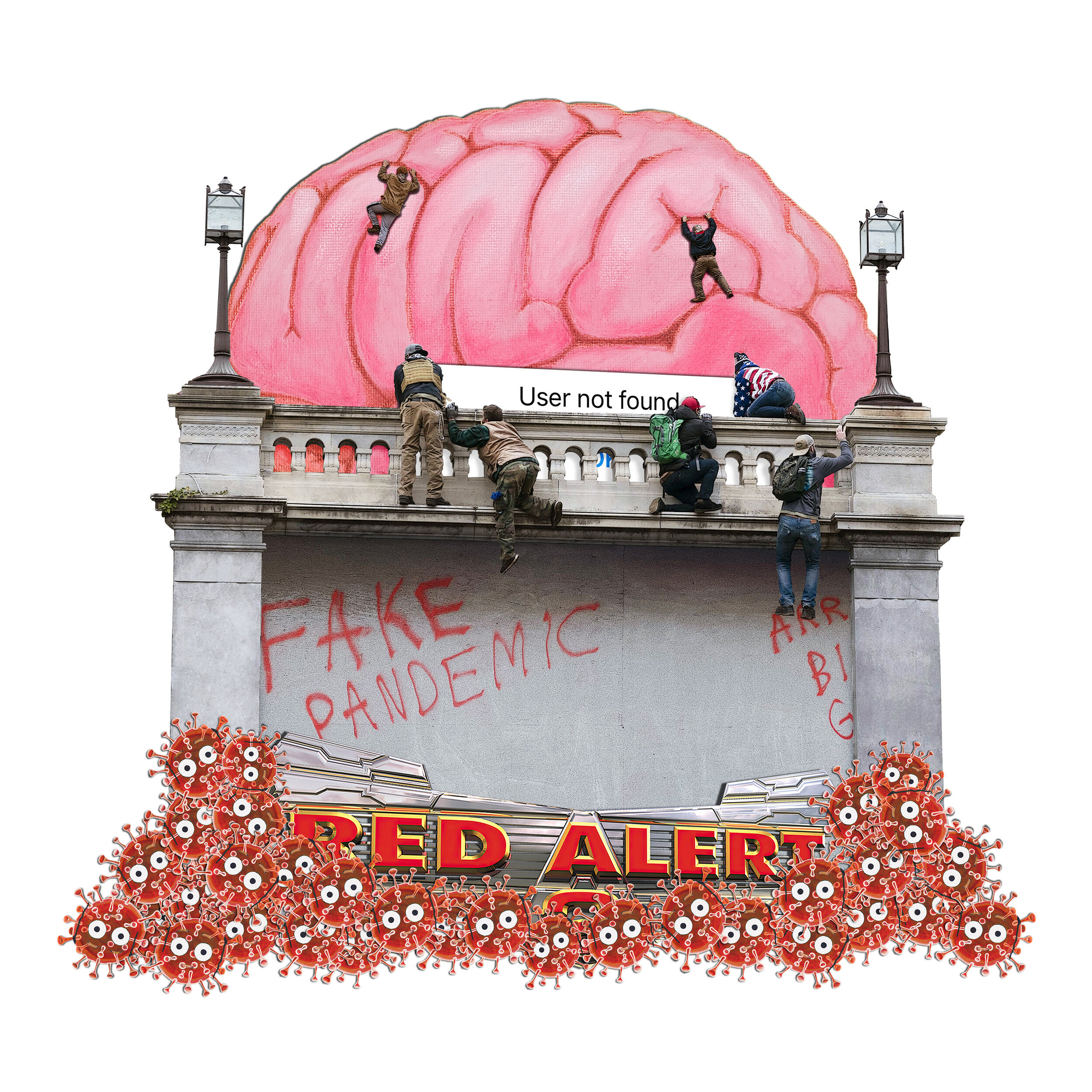

Yuyang Zhang, Red Alert (2021). Hand-cut digital collage on archival paper. 13” x 13”.

Zhang’s screenshots reference our tendency to doomscroll, but also contain coded humor. He repurposes screenshots of Tinder notifications, screen time reports, and shady suggestions from the infamous Co-Star app. There are clear similarities between these phone alerts and propaganda. They’re both meant to capture our attention and serve specific, ongoing narratives. Screenshots also provide visual evidence of our thoughts, ideas, and actions. Posts can be removed by authority, so screenshotting can be a quasi-radical act. We can preserve our content, and thus our ideas, by screenshotting them.

In Deep Clean, Zhang cultivates an environment of toxic masculinity by collaging imagery from a 1966 Zedong propaganda poster alongside a classically gigantic pickup truck. Three men, huddled in a dumpster, wear COVID masks over their eyes. An orange in the background and a screenshot of the words “Delete 45 Items” are both sly digs at Trump.

Red Alert takes a similarly satirical approach. The collage incorporates imagery from two of Zhang’s paintings (a brain emoji and a virus emoji) and blends this with photography from the January 6 Capitol storm. Still more layers include far-right graffiti (“FAKE PANDEMIC”) and a screenshot reference to Trump’s Twitter ban (“User not found”).

Painting is a new medium for Zhang, and his decision to paint emojis follows his decision to use propaganda in his collages. Propaganda is, importantly, simple. Emojis are similarly efficient and easy to understand. They’re both widely available visual languages, and like memes, they both have a “viral” quality. In his This is not Mandarin series, Zhang pairs iPhone emoji paintings with notecards defining a word or phrase in Mandarin. The emojis act as funny entry points toward learning Mandarin—for instance, in the painting Four Seasons, Zhang pairs the surprised emoji with the virus emoji, then layers in references to an iconically nasty Rudy Giuliani photograph and the Four Seasons Total Landscaping press conference fiasco. The Mandarin phrase defined? Sì jì: four seasons.

Yuyang Zhang, Four Seasons (2020). Ink, pastel, and acrylic on canvas. 16” x 20”.

Zhang’s exhibition title, umm no, references an aspiration to say no to authority—Zhang explained in his artist talk that this is not currently an option in China. The phrase also speaks to Zhang’s own development of boundaries in his personal life. At the same time, the word no drives home Zhang’s departure and repurposing of his source content; the original meanings of the emojis and propaganda posters he used have drastically changed. Collage, in a way, is an umm no in practice.

Perhaps most importantly, practicing the act of saying no can be a form of caring for oneself. No has the potential to subvert authority and patriarchy, and Zhang’s works slyly demonstrate this power. Hope is saying no. Hope is trying something different.

~

umm no by Yuyang Zhang is on view at Fuller Rosen Gallery April 15 - May 30, 2021.

Lindsay Costello is an artist, writer, and herbalist-in-training in Portland, OR. She has written art criticism for Hyperallergic, Art Papers, Art Practical, Oregon Arts Watch, and many other publications.