Curatorial Conversation: Uncertainty surrounds the holding of things

Dylan Hester speaks with curators Bella Feinstein and Olivia Miller about themes, artists, and the curatorial process in the exhibition Uncertainty surrounds the holding of things. In a world that privileges immediacy and possession, the exhibition insists on presence and contemplation—a quieting of the mind—to consider the fugitive, errant, unruly lives of things. Featuring sixteen artists from Portland, New York, Germany, Denmark, and Seattle who work with organic, reclaimed, and unruly materials.

Dylan Hester: What do you hope viewers take away from this exhibition?

Bella Feinstein: I was in Los Angeles during the fires last January, witnessing the devastation and the ways in which people responded to their material possessions. What does it mean to have everything destroyed in fire? Where does that place you in relation to the rest of the social world? Uncertainty surrounds the holding of things investigates the human desire to possess and perceive objects and materials.

Olivia Miller: Our relationship to materiality and to our things is always tentative. [We're questioning] the inherent desire to possess things, or to neatly perceive them in a certain way, to have them be permanent.

The title comes from a text by André Lepecki, a curator and writer with a focus on choreography and dance. In the late 2000s, he wrote a text called Moving as something (or, some things want to run). Lepecki defines a "thing" as whatever escapes instrumental reason, whatever exists outside logics of manipulation, whatever is unconditioned, whatever actively wants to run away, escape, from being reduced to graspability and comprehension.

BF: In this exhibition, we see objects such as a bike lock, an ironing board, or a plastic water bottle plucked from their domestic or utilitarian context. Once they pass through the artist's hands, rudimentary traces of their former function become visible. The contrast between the familiar and the unfamiliar invites us to reconsider the object, and begin to reflect on the procedures that went into its making.

(Inge)marmar, for example, presents the head of a rake without a handle. This simple gesture invites us to question the life of an object when its functionality has been stripped. It becomes a commentary on agricultural exploitation, mass-produced products, and an acknowledgement of objects that labor for us.

Al Svoboda is a careful observer of architecture. He often employs plywood to frame or converse with the gallery space, and the plywood is sometimes painted, oscillating between sculpture and painting. For the exhibition, Svoboda presents a video, which one of these plywood paintings is bent and snapped. The panel, it could be said, is choreographing his movement, determining his gestures.

DH: As objects lose their usefulness, they tend to turn into something else. What happens when objects become 'used-up' and discarded?

OM: Nate Millstein's practice is based on making casts of everyday items that fall to the wayside, or exit this cycle of production, consumerism, depletion—objects that lose their use value.

BF: Objects that previously labored for us. That's a thread that we were trying to harp on throughout: how can these materials be reanimated?

OM: Throughout the curatorial process, we both grappled with the contrarian idea of permanence. Many of the artists here use temporal mediums, which are subject to change – even over the course of our exhibition. We were focused on the precarity of these materials and the ways that the artists surrender to their agential objecthood.

Rachel Wolf's mobiles, for example, are a language of keeping. She collects and forages detritus to build a new ecology. The artist places elements that are living, nonliving, perishable, or newly dead into a wire frame that leverages them, making them precious. It's very poetic in how it connects all these disparate objects. You get her sense of collecting and foraging.

DH: Could you talk about the relationships between artists and how those relationships influenced your curatorial process?

OM: Our show evolved over many conversations. Lots of talking through things, and sharing ideas and references.

BF: The group show accentuates a lot of the organic relationships that exist amongst artists already. And that's been important to us as facilitators of this show – that these works and artists have relationships beyond just this experience.

OM: It was really nice to let the exhibition unfold in organic ways, especially because we don't have our feet on the ground in the Pacific Northwest, so being able to rely on the community amongst the artists, and see whose works responded naturally, was very exciting.

DH: An artwork is what is left behind in the wake of creative labor. It is material proof of the artist’s thinking, process, and action. Could you talk about how many of these artworks feature objects that carry hidden histories that may not be immediately apparent?

BF: Francesca Lohmann works with sausage casings to create amorphous, anthropomorphic figures. The shape and consistency of the object change throughout that process, throughout the drying. [These are] supported with memory foam pieces, and the memory foam changes over time as well. Entropy plays a large role in her work because of the ways that time changes the function of something, and that's not the time that we all subscribe to. There's an undercurrent in this show about memory [and] latent history. manuel arturo abreu’s practice is fully motivated by concepts of memory and capturing that.

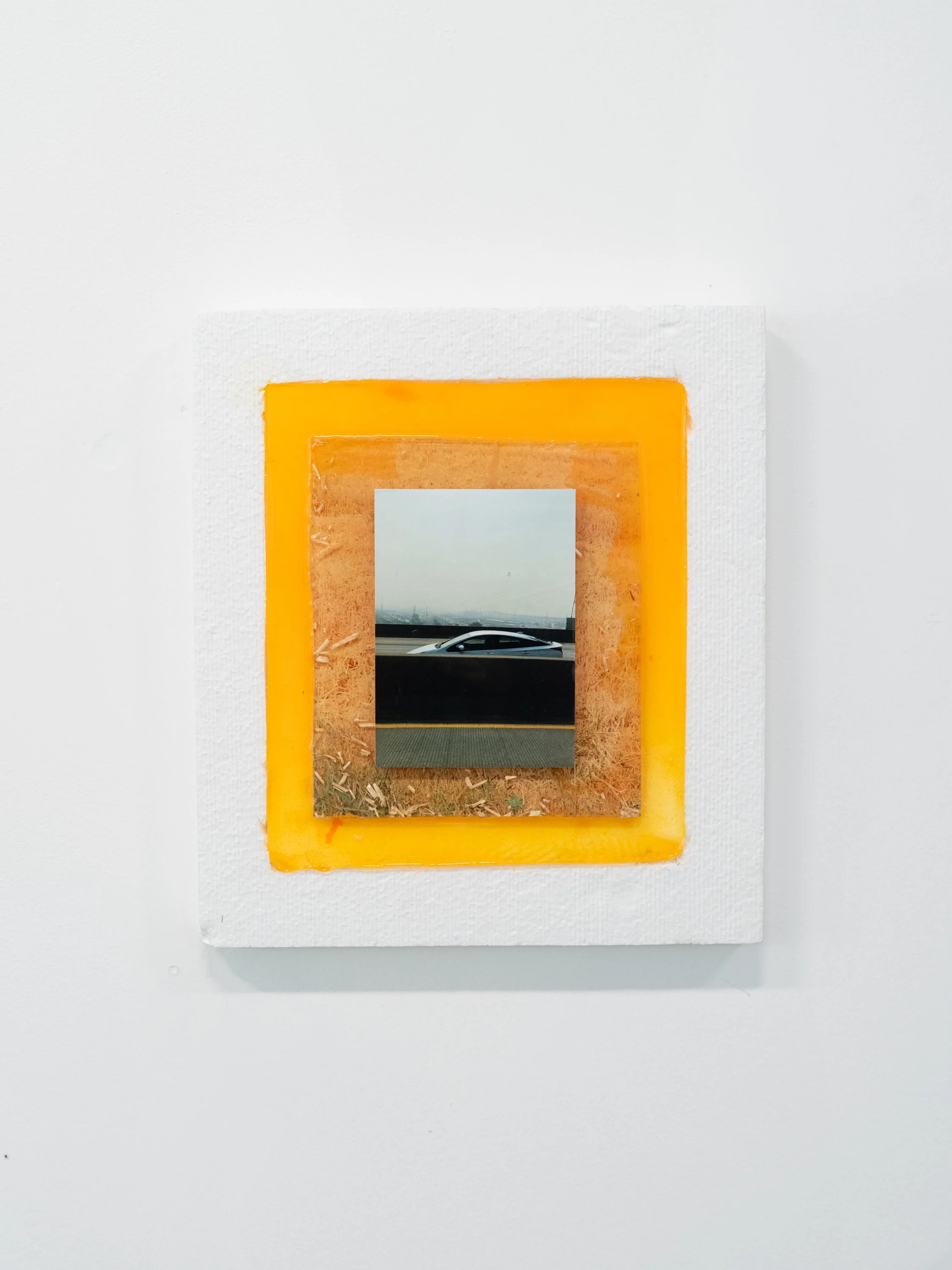

OM: Yeah, manuel’s work exists in this body of exploring the latent histories and meanings that materials accrue over time. There is a connection there to Epiphany Couch. Epiphany [utilizes] discarded family images and found materials to create these works. Her practice at large is extremely attuned to the stories and histories that materials can carry, through generational story telling, memory, or cultural osmosis. It makes us think about what meaning we extract from things that previously belonged to someone, that still hold the residue of a past life.

BF: Working with florals in any capacity is like this. A complete confrontation with permanence, and this idea that the flowers are already dead by the time that they're being constructed or presented. There is this notion of entropy [or] decay, but also, is there still vitality when something is in that process?

OM: We’re thinking about matter and time and ideas of permanence. Value or materiality over time.

DH: For some, time is the medium itself. Prague-based choreographer Marketa Fagan created a time-based dance piece. Could you talk about this work in more detail?

BF: Marketa executed a series of movements, without any protection, through these beehives. The video is set to the sound of birds, and the pace at which she's moving is incredibly slow, attuned to every part of every limb of the body. It challenges this idea of time as a material possession. It requires careful viewing. These artists are urging us to change our perception of objects and the built environment. We are asking our viewers to do some work, to think about the ways that they perceive things in their day-to-day life. What happens when you break that framing? Where can you create new meaning and new understanding?

What holds these sixteen artists together is their embrace of uncertainty, entropy, and change. This exhibition reminds us that the ways we approach objects are never simple or neutral. Can we change these objects by changing how we perceive them? And will they change us in the process?

Uncertainty surrounds the holding of things opens November 14 and runs through December 20th at after/time collective in Portland, Oregon.

This discussion has been edited for clarity.